Interval training has received lots of attention in the media, but does it really provide superior fitness benefits? The answer is yes but mostly no. This is also termed High Intensity Interval Training. In terms of pure physiology, not so much of a new concept as a marketing phrase designed to increase appeal to sell programming/classes or equipment.

Interval training is simply alternating some increased intensity activity with some type of recovery, or l0wer level activity. For example, in walking you could walk up a steep hill for one minute, then casually stroll down the hill for one minute, then repeat. By broad definition, anything where there is a higher intensity/difficulty/speed period that is balanced by a lower level of the same 0r complete rest fits the definition. That is half the issue in comparing interval training results, there are quite a few variations all with different physiological nuances and uses.

Historically, interval training had a boost when fitness activities increased in the 70’s and 80’s. It was easy for athletic facilities to take a row of machines, and put some type of recovery or moderate activity between each weight station. That was generally a trampoline, running in place or a stationary bicycle. The weight training was theoretically the high intensity activity (or some type of body-weight movement), while the aerobic activity was supposed to either keep your heart rate up or provide recovery. That was really the start of promising better fitness results in less time.

This also became known as circuit training, and almost all athletic clubs/facilities have some kind of circuit in their training area. Strength circuits of this nature have come and gone and are back again in popularity and usage. Group cycling provided the largest organized push with interval training. At first, not by design, but by promising a difficult workout with motivational music. One must remember when you are in the fishbowl of group cycling, you can’t leave the class very easily without the whole group noticing your departure. In the last 10 years, group cycling has really jumped on the interval tandem.

At the same time, CrossFit gained popularity due to the same promises of an overall, muscle and energy system workout. Covid also resulted in people getting apps and videos at home to take light weights and body weight exercises and alternate them in some format. A myriad of converging messages that you should do interval training.

Like most things in human physiology, there has been a significant amount of research about fitness benefits of these various forms of interval training. One of the most studied aspects of these programs is the promise of increased strength in less time that traditional resistance training. Down to the muscular gritty, a muscle needs significant work, then adequate recovery. A research-based generalization would be to gain strength, one needs to lift a weight or resistance they can only perform 10-12 times, then rest for 60-75 seconds and perform additional sets.

In circuit programs, the weight is greatly reduced based upon a time to work the muscle, like 45 seconds, with a short period between exercises of sometimes only 20 seconds. The research is really clear on this one, you gain a little bit of strength, but much, much lower compared to traditional resistance training. The reason is not enough resistance and not enough recovery. Additionally, the aerobic recovery compromises the muscle’s ultimate strength gain.

An off-shoot conclusion from these studies was that a circuit approach was useful in someone starting a fitness program. However, the results from combining both resistance and aerobic work capped at about three weeks. After that, people were better off with separate training sessions of strength or aerobic training if they wanted to get beyond a basic fitness increase.

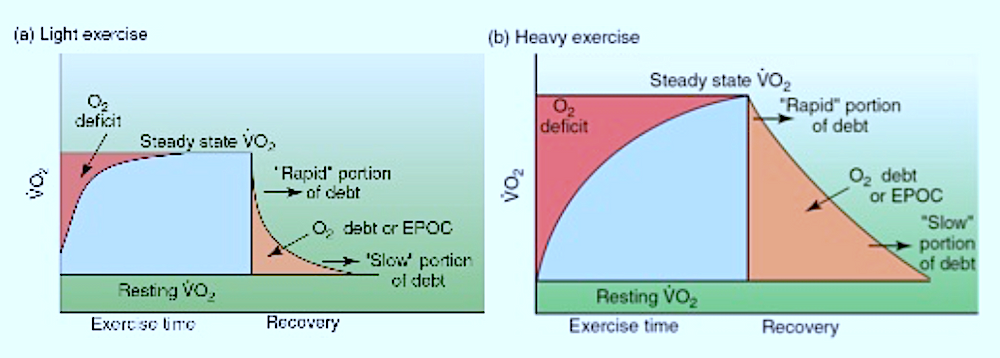

Does your metabolism increase from Interval Training? A lot of the hype has been that Exercise Post Oxygen Consumption or EPOC, the rise in metabolism to replenish lost energy stays elevated for hours. The initial research started in the 90’s and the measurement equipment was not as good as current technology, and interval training and results were not near as defined. The results were limited in application. However, as a general observation, the EPOC idea lost a large amount of caloric justification because the measurements did not prove current lore and promises.

In most studies, resting metabolism was only slightly elevated after exercise, and that was for a short period of 15-30 minutes. Also important to consider is that the athletes will be at the shorter end of that time scale, while those with less than moderate levels of fitness will be closer to the 30 minute mark. However, it’s definitely not hours, and not 100’s of calories. And more importantly, it does not add significantly to the actual energy burned in the exercise itself. That is the most important consideration in this regard.

In testing thousands of athletes, I can tell you from personal experience and the data, that after a VO2 max test, most of the athletes were fully recovered in five minutes. Joe and Jill Exerciser were normally recovered in in 10 minutes. And, the caveat to to this finding is that with moderate or greater fitness levels, recovery from maximal exercise is much quicker in this sense. Out of shape, and it’s 30 minutes in the recliner no matter what you do in exercise.

Does HIIT burn significantly more kcal than cardio training? In our short research study, we confirmed that interval training and cardio training came out almost equal in how many kcal you burn per hour. We used an Oxycon Mobile measurement system to measure actual kcal burned to determine if interval training burned more energy that aerobic/”cardio” training. It’s a matter that the intervals balance with the recoveries in terms of energy expenditure.

The real benefit of interval training is not the kcal you actually burn, but that you increase your ability to burn more kcal in steady state training. In technical terms, you elevate your Anaerobic Threshold. So, when you hop on that elliptical you can burn 10 kcal a minute versus 7 kcal a minute. Over 50 minutes, that really adds up in terms of weight loss, fitness benefit and even overall health.

So, use interval training once or twice per week, and spend the balance of time in steady-state/”cardio” training and that will likely provide an optimal fitness benefit.

Select References

LaForgia J, Withers RT, Gore CJ. Effects of exercise intensity and duration on the excess post-exercise oxygen consumption. J Sports Sci. 2006;24(12):1247-1264.

Quinn TJ, Vroman NB, Kertzer R. Postexercise oxygen consumption in trained females: effect of exercise duration. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26(7):908-913.

Børsheim E, Bahr R. Effect of exercise intensity, duration and mode on post-exercise oxygen consumption. Sports Med. 2003;33(14):1037-1060.

Tsirigkakis S, Mastorakos G, Koutedakis Y, et al. Effects of Two Workload-Matched High-Intensity Interval Training Protocols on Regional Body Composition and Fat Oxidation in Obese Men. Nutrients. 2021;13(4):1096.

Schmidt D, Anderson K, Graff M, Strutz V. The effect of high-intensity circuit training on physical fitness. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2016;56(5):534-540.

Weston M, Taylor KL, Batterham AM, Hopkins WG. Effects of low-volume high-intensity interval training (HIT) on fitness in adults: a meta-analysis of controlled and non-controlled trials. Sports Med. 2014;44(7):1005-1017.

Short KR, Sedlock DA. Excess postexercise oxygen consumption and recovery rate in trained and untrained subjects. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1997;83(1):153-159.

Schaun GZ, Pinto SS, Praia ABC, Alberton CL. Energy expenditure and EPOC between water-based high-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity continuous training sessions in healthy women. J Sports Sci. 2018;36(18):2053-2060.

Martínez-Rodríguez A, Rubio-Arias JÁ. Effects of Resistance Circuit-Based Training on Body Composition, Strength and Cardiorespiratory Fitness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biology (Basel). 2021;10(5):377. Published 2021 Apr 28.

Hortobágyi T, Katch FI, Lachance PF. Effects of simultaneous training for strength and endurance on upper and lower body strength and running performance. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1991;31(1):20-30.

Häkkinen K, Alen M, Kraemer WJ, et al. Neuromuscular adaptations during concurrent strength and endurance training versus strength training. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2003;89(1):42-52.